Missing Data

Missing data can be tricky and problematic, but profiling patterns of missingness in a dataset need not be.

We will be using the following packages in this section.

install.packages(c("tidyverse","here","naniar"))Missing Data

Missing data can be tricky and problematic, but profiling patterns of missingness in a dataset need not be.

We will be using the following packages in this section.

install.packages(c("tidyverse","here","naniar"))Don't forget to load the packages after the install is complete.

library(tidyverse)library(here)library(naniar)Missing Data: Load the Data

# Run the entire cleaning script to reproduce our cleaned version of the superhero datasource(here("scripts","cleaning_script.R"))## Parsed with column specification:## cols(## X1 = col_double(),## name = col_character(),## Gender = col_character(),## `Eye color` = col_character(),## Race = col_character(),## `Hair color` = col_character(),## Height = col_double(),## Publisher = col_character(),## `Skin color` = col_character(),## Alignment = col_character(),## Weight = col_double()## )Let's Take a Peak at the Data

# Take a peak inside to ensure that it was loaded correctlyglimpse(data_superhero)## Rows: 734## Columns: 13## $ id <dbl> 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14...## $ name <chr> "A-Bomb", "Abe Sapien", "Abin Sur", "Abomination...## $ gender <chr> "male", "male", "male", "male", "male", "male", ...## $ eye_color <chr> "yellow", "blue", "blue", "green", "blue", "blue...## $ race <chr> "human", "icthyo sapien", "ungaran", "human / ra...## $ hair_color <chr> "no hair", "no hair", "no hair", "no hair", "bla...## $ height <dbl> 203, 191, 185, 203, NA, 193, NA, 185, 173, 178, ...## $ publisher <chr> "marvel comics", "dark horse comics", "dc comics...## $ skin_color <chr> NA, "blue", "red", NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, N...## $ alignment <chr> "good", "good", "good", "bad", "bad", "bad", "go...## $ weight <dbl> 441, 65, 90, 441, NA, 122, NA, 88, 61, 81, 104, ...## $ gender_fct <fct> male, male, male, male, male, male, male, male, ...## $ alignment_fct <fct> good, good, good, bad, bad, bad, good, good, goo...

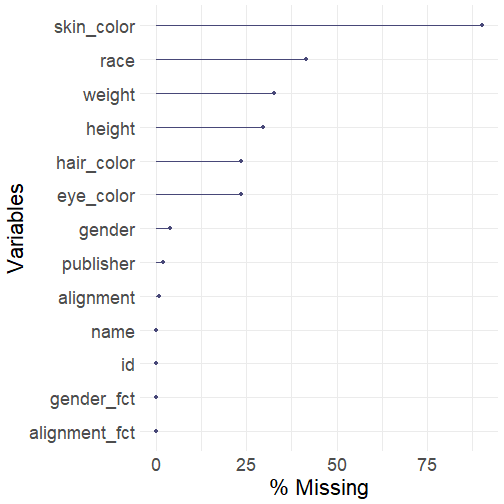

Visualize Missingness by Column

Visualize Missingness by Column

# generate missing data visualization by columnsgg_miss_var(data_superhero, show_pct = TRUE)

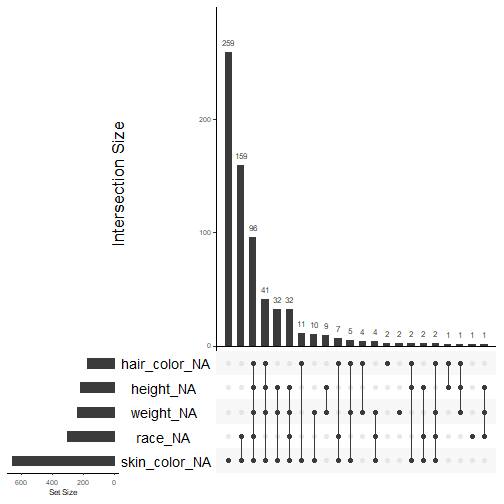

Visualize Intersections of Missingness

While understanding how much data is missing in each column is important information, when trying to find patterns of missingness you need to examine the intersections of missingness.

Visualize Intersections of Missingness

While understanding how much data is missing in each column is important information, when trying to find patterns of missingness you need to examine the intersections of missingness.

In essence, we might want to know the percentage of our data which has missing weight and height.

Visualize Intersections of Missingness

While understanding how much data is missing in each column is important information, when trying to find patterns of missingness you need to examine the intersections of missingness.

In essence, we might want to know the percentage of our data which has missing weight and height.

This could help us when we make assumptions about patterns of missingness.

Creating an Upset Plot

gg_miss_upset(data_superhero, nsets = 5, nintersects = NA, text.scale = c(2,1,1,1,2,1.3))We need to specify the dataset we want to use, the number of sets (which variables) to include, and the number of interactions we want to examine.

If you set the ninteractions arugment to NA, then all interactions using the given variables will be displayed.

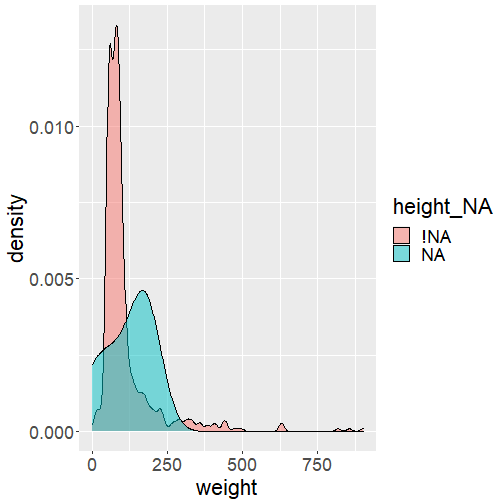

Shadow Matrix

A handy way to examine conditional missingness is to construct a shadow matrix (Swayne and Buja, 1998). This matrix has the same dimensions as the original dataset, but each column now has a parallel column which tracks the missingness of its partner.

There are two ways of quickly constructing the shadow matrix: one way creates the matrix as a new dataset, the other appends the shadow matrix to the original dataset column-wise.

# create a shadow matrix of the superhero datasetas_shadow(data_superhero)# add the shadow matrix to the side of the superhero datasetbind_shadow(data_superhero)

Shadow Matrix: Profiling

data_superhero %>% bind_shadow() %>% ggplot(aes(x = weight, fill = height_NA)) + geom_density(alpha = .5)- Start with the superhero dataset, then ...

- append the shadow matrix, then ...

- construct a canvas using weight on the x-axis, and fill by using whether height is missing or not, then ...

- generate a density plot with some transparency

Working With Dates, Times, and Date-Times

Working With Dates, Times, and Date-Times

Dealing with dates can be tricky as there are many ways to write a date.

I recommend changing your dates to align with the ISO 8601. The general principle behind this standard is ordering the date/time from the largest units to the smallest units. Adhering to this standard makes it clear how your data is stored and makes it easier to use.

- 2020/03/04: is this March 4th, 2020; or April 3rd, 2020?

- 20/03/05: is this March 20th, 2005; or June 3rd, 2020?

Unless you document how the date is stored, only you will know the correct date.

The lubridate package has many handy function for managing three kinds of data:

- date-time: which is stored as the number of seconds since 1970-01-01 00:00:00 UTC

- date: which is stored as the number of days since 1970-01-01

- time: which is stored as the number of seconds since 00:00:00

Lubridate

Let's try an example. This fictitious data was "collected" in March of 2020 across two different collection sites (A and B). We can start by loading the "date_time_data.csv" file and taking a peak.

library(lubridate)data_dates <- read_csv(here("data", "date_time_data.csv"))## Parsed with column specification:## cols(## id = col_double(),## date = col_character(),## time_collected = col_time(format = ""),## site = col_character()## )Pro-Tip: Excel Dates

It can happen that dates stored in excel files are treated as numeric. One way to get around this is to convert using the as.Date() function from base R and alter the origin argument.

# excel commonly uses an origin of 1899-12-30 for storing dates as a numberas.Date(43900.00, origin = "1899-12-30")## [1] "2020-03-10"

Lubridate: Parsing Dates

Looking at our data, it seems that "Site A" and "Site B" used different conventions for storing the dates. Right now, the dates are both stored as character data. We will need to take care when converting them in order to continue working with them error-free.

You can specify the format ordering using the following key:

- year (y)

- month (m)

- day (d)

- hour (h)

- minute (m)

- second (s)

Lubridate has many parsing functions that are simply combinations of the keys above which reflect the date format in your data.

Lubridate:: Parsing Dates

The lubridate has many built-in functions using a variery of common formats. For example, one could use the function ymd_hms() to convert a string or number into a year, month, day, hour minute second date-time object. One could also use ymd() for a date object, or hms() for a time object.

# If we assumed that all of the dates followed the format year month dayymd(data_dates$date)## [1] "2020-03-10" "2020-03-11" "2020-03-12" "2020-03-13" "2020-03-14"## [6] "2020-03-15" "2020-03-16" "2017-03-20" "2018-03-20" "2019-03-20"## [11] "2020-03-20" "2021-03-20" "2022-03-21" "2023-03-20" "2024-03-20"# If we assumed that all of the dates followed the format day month yeardmy(data_dates$date)## [1] "2010-03-20" "2011-03-20" "2012-03-20" "2013-03-20" "2014-03-20"## [6] "2015-03-20" "2016-03-20" "2020-03-17" "2020-03-18" "2020-03-19"## [11] "2020-03-20" "2020-03-21" "2021-03-22" "2020-03-23" "2020-03-24"

Lubridate:: Parsing Dates

Let's use a handy function from the dplyr package dplyr::case_when. It operates similar to the dplyr::if_else() function we used in section one, but it permits us to check multiple conditions within the one function.

Each argument is an expression. The left-side of the expression is a logical comparison, when that comparison evaluates as true, then that rows value becomes the value from the right-side of the expression.

# fix the dates depending on which site and the format that was useddata_dates %>% mutate(date_corrected = case_when(site == "Site A" ~ ymd(date), site == "Site B" ~ dmy(date), TRUE ~ NA_Date_))As a rule, always include an additional "catch-all" argument for in case a value being transformed doesn't meet any of the other criteria.

Also note, that there special types of missing data that follow the form NADate

Lubridate

| id | date | time_collected | site | date_corrected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 20-03-10 | 10:03:00 | Site A | 2020-03-10 |

| 2 | 2 | 20-03-11 | 12:47:00 | Site A | 2020-03-11 |

| 3 | 3 | 20-03-12 | 15:59:00 | Site A | 2020-03-12 |

| 4 | 4 | 20-03-13 | 08:43:00 | Site A | 2020-03-13 |

| 5 | 5 | 20-03-14 | 07:00:00 | Site A | 2020-03-14 |

| 6 | 6 | 20-03-15 | 11:03:00 | Site A | 2020-03-15 |

| 7 | 7 | 20-03-16 | 11:47:00 | Site A | 2020-03-16 |

| 8 | 8 | 17-3-20 | 10:03:00 | Site B | 2020-03-17 |

| 9 | 9 | 18-3-20 | 10:30:00 | Site B | 2020-03-18 |

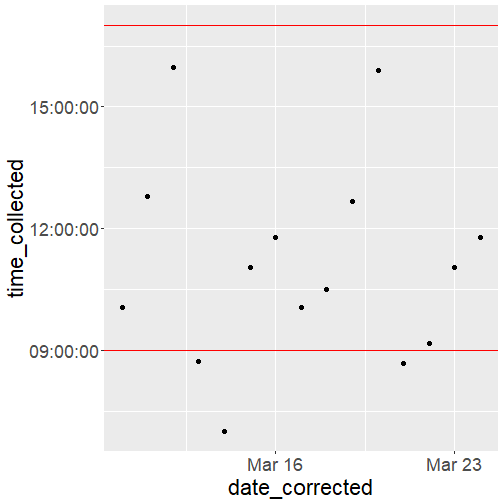

Lubridate: Intervals

We can also check that all dates fall within a valid range of dates.

# define a valid interval for data collectiondata_collection_period <- interval(ymd("2020/03/01"), ymd("2020/03/31"))data_dates %>% filter(!(date_corrected %within% data_collection_period))## # A tibble: 1 x 5## id date time_collected site date_corrected## <dbl> <chr> <time> <chr> <date> ## 1 13 22-3-21 09:10 Site B 2021-03-22

Lubridate: Getting and Setting

The lubridate package provides many handy functions getting and setting components of date, time, and date-time values. These can be useful for correcting specific dates (either by over-writing the incorrect piece of the date or by incrementing the date by specific values).

# create a date-time to use for this exampledate_time_example <- ymd_hms("2020-07-26 10:00:00")date_time_example## [1] "2020-07-26 10:00:00 UTC"# extract the year componentyear(date_time_example)## [1] 2020# change the year to 2019 because we are all tired of 2020year(date_time_example) <- 2019date_time_example## [1] "2019-07-26 10:00:00 UTC"

Lubridate: Date Arithmetic

There are functions which can add periods of time by pluralizing the functions we use for getting and setting values (e.g., year() vs. years()).

Let's fix that futuristic date collected from "Site B".

# manually correct the one date of collection fromthe future (year == 2021)data_dates %>% mutate(date_corrected = if_else(condition = year(date_corrected) == 2021, true = date_corrected - years(1), false = date_corrected))

Lubridate: Visualizing Dates and Times

data_dates %>% ggplot(aes(x = date_corrected, y = time_collected)) + geom_point() + geom_hline(yintercept= hms("09-00-00"), color = "red") + geom_hline(yintercept= hms("17-00-00"), color = "red") + scale_y_time() + scale_x_date() + theme(text = element_text(size = 22))

Take Home Message

- Understanding how, why, and where your data is missing is crucial

- We might not ever know for sure why data is missing, but examing where it is missing could help us with our assumptions about missingness

- Importing dates into R from Excel can be tricky

- Always check that the dates are still correct

- Using intervals can be a great way to check

Resources:

Naniar Package: http://naniar.njtierney.com/index.html

Lubridate:

- Blog post - https://lubridate.tidyverse.org/

- Cheat Sheet - https://github.com/rstudio/cheatsheets/raw/master/lubridate.pdf

- R4DS Book Chapter - http://r4ds.had.co.nz/dates-and-times.html